Let's salute to our Indian Army together, We are proud to be Indian.

Let's salute to our Indian Army together, We are proud to be Indian.

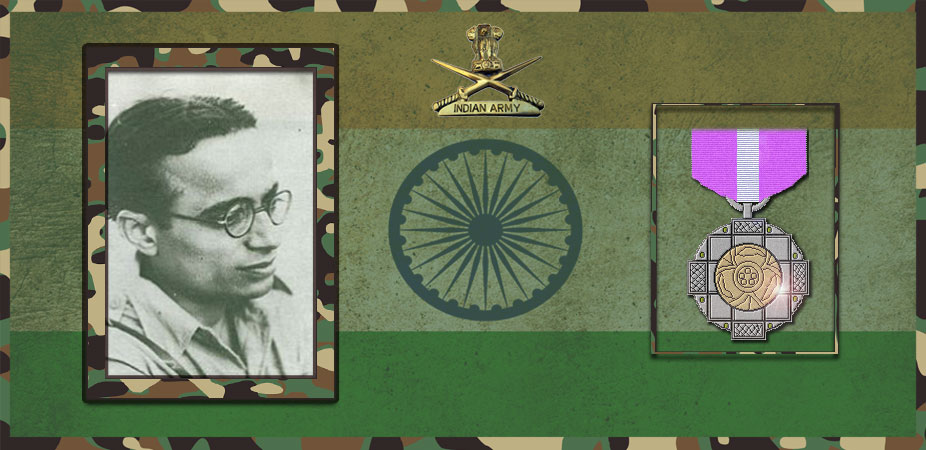

Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia (હસમુખ ધીરજલાલ સાંકળિયા) (10 December 1908 – 28 January 1989) was an Indian archaeologist, specialising in Proto- and Ancient Indian history. He is considered to have pioneered archaeological excavation techniques in India, with several significant discoveries from the Prehistoric period to his credit. He was awarded Ranjitram Suvarna Chandrak in 1966.

Sankalia was born in Mumbai into a family of lawyers hailing from Gujarat. As a frail infant, the doctor did not expect him to survive long.

At the age of fifteen, he read the Gujarati translation of Lokmanya Tilak’s The Arctic Home in the Vedas. Though he did not understand much of it, as he said it himself (p. 6), he was determined to ‘do something to know about the Aryans in India’ (ibid.). He therefore decided to opt for Sanskrit and Mathematics for his B.A. because these were the subjects sound knowledge of which was a must for one who wanted to trace the origin of the Aryans (Tilak himself was a great Sanskritist and a Mathematician). This was a turning point Sankalia’s life. In B.A. he opted for Sanskrit. By that time, he had already acquired a sound knowledge of Sanskrit, and bagged the Chimanlal Ranglal Prize for scoring highest marks in that subject in Matriculation. Later on, though he was occupied more with Prehistory, his ‘life work’, the problem of the Aryans was never lost sight of: his ingenious interpretation of the Chalcolithic cultures of Rajasthan and Central India to be of an Aryan origin was largely influenced by his background. He always considered the Aryan Problem as of prime importance(1962c: 125; 1963a: 279-281; 1974: 553-559; 1978a: 79, etc.). He opted, determined as he was, for Sanskrit and voluntary English for B.A.; the latter subject introduced him to textual criticism (p. 7), which again was a powerful tool to interpret the original texts in a critical way. With the sound knowledge of Sanskrit and textual criticism, he could write an excellent article on ‘Kundamala and Uttararamacarita’, in which he convincingly proved that Dinnaga, the author of the former, influenced the author of the latter.A Bengali scholar, K. K. Dutt, arrived at similar conclusion, quite independently of Sankalia.It was in the light of the latter that Sankalia published a revised edition of his earlier paper (1966a).

Having passed his B.A. with Sanskrit, Sankalia switched on to Ancient Indian History for M.A. at the newly set up Indian Historical Research Institute (now, Heras Institute), and chose to work on the famous ancient university of Nalanda for his M.A. Dissertation. It was a multi-faceted topic with separate chapters on History, Art and Architecture, Iconography, influence of Nalanda school of art on the Greater India, especially Java, etc. Sankalia was thus forced to dwell into each of these.He performed his task remarkably under the supervision of Heras. He visited a number of sites with Heras and acquired a thorough knowledge of the subject. Heras himself was an Indologist of some note and influenced the young Sankalia considerably. Sankalia likewise studied the tenets of Buddhism with no less than an authority like B. Bhattacharya (p. 10). This exposure to Art, Architecture, Iconography and Archaeology in general proved to be of great importance, a kind of initiation to his later study of Gujarat. It was this in-depth study of the classical branches of archaeology, which made him equally at home in Historical Archaeology. His study of Nalanda earned him the degree of M.A. and the Chancellor’s Medal. Sankalia simultaneously passed his LLB examinations, according to the wishes of his father and uncle, who were both lawyers. Subsequently, he was expected to follow the same occupation (cf. pp. 10, 13, 28). But Sankalia did not agree to this; at the suggestion of his teacher, Heras, he made up his mind to go to England for his Doctorate. Meanwhile, he wrote an essay on the ‘Caitya caves in the Bombay Presidency’, which got him the prestigious Pandit Bhagavanlal Indraji Prize and Gold Medal.

After coming back to India, Sankalia joined, in 1939, Deccan College as Professor in Proto and Ancient Indian History. From Deccan College, Sankalia started systematic surveys of the monuments in and around Pune with his pupils. Sankalia’s explorations resulted in his papers on the Megaliths of Bhavsari and on the Temple of Pur of the Yadava period.At the instance of the then Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, K. N. Dikshit, Sankalia undertook explorations in Gujarat to prove or reject the hypothesis put forward by Bruce Foote of a hiatus between the Lower Palaeolithic and Neolithic phases.This experience turned him into a prehistorian, and since then he never looked back.

He also engaged other expeditions in Gujarat subsequently. In the second expedition, he found the first ever-discovered human skeleton of the Stone Age Man. The Mesolithic site of Langhnaj – ‘the first Stone Age site to have been excavated scientifically’ – was excavated stratigraphically. Prof. Zeuner, an acclaimed authority on environmental archaeology, was invited at the instance of Wheeler, to interpret the palaeoclimate of Gujarat. Sankalia was profoundly influenced by this scholar, from whom he learnt the lessons of geochronology, geology, stratigraphy of geological deposits and the mechanics of Pluvial and Inter–pluvial. Sankalia fully utilized this knowledge while interpreting other prehistoric sites, which he or his staff explored or excavated.

The historical site of Kolhapur was excavated in 1945-46 with M. G. Dikshit (Sankalia and Dikshit 1952). However, before this excavation, his detailed surveys on the banks of Godavari and its tributaries revealed a flake tool industry. These findings were also observed in a stratigraphical deposit at Gangapur (Gangawadi) near Nasik. Here, an assemblage consisting of flakes, cleavers and hand axes was discovered. This well developed Palaeolithic industry, as later researches proved it beyond doubt, was the Middle Palaeolithic. His explorations in the Pravara valley at Nevasa yielded Palaeolithic industries with animal fossils.

The occurrence of Northern Black Polished Ware at Nasik – which has also been mentioned in the Puranas and traditional tales – as reported to Sankalia by M. N. Deshpande, made him anxious to discover at the site evidences that could be correlated to the Early Historical Period, and also if possible, to unearth pre- and proto-historic cultures.The excavation was carried out and the aims were by and large fulfilled.

Sankalia after the retirement opted to reside on the campus. He was appointed Professor Emeritus in the Department. Retirement or old age could not stop him from his researches on Early Man; he in his own residence discovered what he believed were Palaeolithic implements. He also brought out his famous studies on the Ramayana,New Archaeology,and Prehistoric Art during these years.

At the ripe age of 80, he breathed his last on 28 January 1989.

Sankalia was also enthusiastic about several extra-academic activities. He invariably captained one of the cricket teams on College Day. He was equally interested in kite flying; Ravindra Sankalia, his nephew, narrates one incident in which his uncle cut down as many as 40 kites without losing theirs. In his leisure time, Sankalia was an ardent gardener. His students bore him love and respect both, with many of them receiving unstinted affection and help. He was thus a scholar, a guru, an acharya – in both the etymological and semantic sense – a lovable and respected human being and an enlightened citizen of India.